On the morning of 17th March 1925, RMS Tahiti arrived in Wellington, New Zealand from San Francisco[1] and anchored off Kaiwharawhara, in Port Nicholson. Its human cargo transferred itself to the Janie Seddon, and this smaller vessel proceeded to Pipitea Wharf, where throngs of happy people had gathered. They were accompanied by an animated herd of pressmen and photographers all busily jostling for position, and as the ferry came to rest and the passengers disembarked, a band struck up See The Conquering Heroes. After circumnavigating the world, the 1924 All Blacks were home at last.

In those days, and up until the mid-1980s, overseas sports tours lasted months not weeks, and New Zealand’s national rugby team had been away from home for three seasons of the calendar. These days, tour costs are paid by corporate sponsors and huge broadcasting fees, in those days, costs had to be covered, and profits made, by getting feet through turnstiles. Therefore, touring teams had to play two, and often three, dozen games.

The All Blacks had left Wellington aboard RMS Remuera on 29th July - with the vessel commanded by Capt. J.J. Cameron, the same man who was Chief Officer of S.S. Rimutaka the ship that had carried the ‘Original’ All Blacks to Britain in 1905. They arrived at Plymouth, Devon on 2nd September, and ahead of them was a schedule of 28 matches in the British Isles - though none in Scotland because of intransigent SRU officialdom - with Tests against Ireland and Wales before a finale against England who at the time, were undisputed champions of Europe. Four other matches, including two in France were scheduled for a convoluted journey home: a shuttle over to France and back, and then a journey to Liverpool to board the trans-Atlantic liner SS Montlaurier which carried them to Canada for their odyssey to Vancouver, followed by a journey overland to San Francisco and thence home.

The people at the Pipitea pierhead had not just gathered to welcome their friends and loved ones, the masses were there to see heroes and pay homage. To NZ’s 1.3m people, these men were indeed conquering heroes, much like the returning soldiers of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force had been in 1918-19. They had played 30 matches against English, Irish, Welsh and French teams - plus two games in Canada - and had remained unbeaten. They were the ‘Invincibles’.

The radio age had barely begun, and even in England, the broadcast of live sports matches was still two years away. Yet despite the distance, everyone at the quayside knew the results and details of the tour. NZ was a small country a very long way from the world’s busiest cities, but foreign news, was relayed by telegraph and printed in local newspapers. News from the contents of players’ letters home would also have circulated through communities both urban and rural. For the whole country, their spring and summer had been dominated by sports news from the Old Country. Like Australians and their cricket teams, rugby was of huge significance to New Zealanders, tucked away in a small corner, on the far side of the planet, it was how they reminded Britons of their existence, and proved to them that they were thriving.

Sport mattered, for it told the world about Antipodeans and proved their many qualities. There was also a political element attached to the importance of winning. In the late-Victorian age and into the twentieth century, sport - principally cricket and rugby - was used as a tool to bind the Empire. Mostly, it was played in Corinthian spirit, but national pride was of vital importance, especially when the RFU attempted to ‘lay down the law’[2].

Rugby was important domestically too, representing a Kiwi province at rugby was not just a mark of skill and athleticism, it was a social label. The status carried not only popularity and privilege, but also dignity and duties - duties to preserve the honour of the regional community, and to maintain personal discipline in all aspects of life both on and off the field. Being an All Black rugby player enhanced such circumstances substantially, wearing the ‘silver fern’ carried five-fold the kudos, and those responsibilities were multiplied by the same measure. Doing damage to a provincial shirt might seriously harm one’s prospects in one’s community, but anyone dishonouring the national jersey might have been made a social outcast.

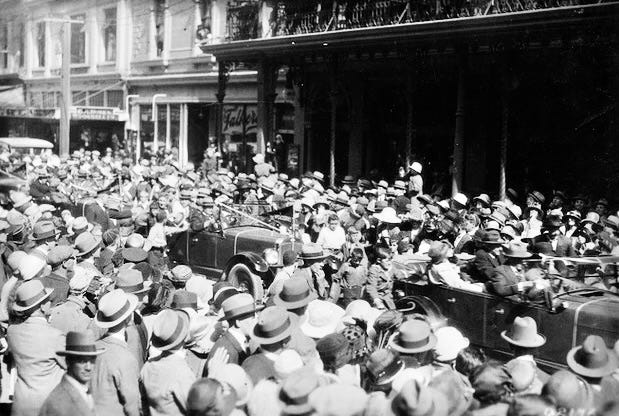

Welcoming the tourists home, Mr. G. Mitchell the Harbour Board chief, said, “…..the All Blacks were the greatest asset NZ had had…..we are proud of your unbeaten record. You have silenced the critics, both in this country and abroad…..You are our heroes, and as heroes shall you always be remembered in the history of our country”[3]. The team manager, Mr. Stanley Dean, made a brief statement of reciprocal salutation and then, upon the crowd’s request, the team performed a haka. After this, in early-autumn sunshine, they boarded open-topped cars to travel to an early luncheon at the Town Hall. The journey was short, but slow, for they were led by the band and lauded all the way down Lambton Quay by many thousands of deliriously happy Wellingtonians.

Wellington, Lambton Quay - the Invincible All Blacks are Welcomed Home

However, there was one amongst their number who may not have felt quite so relaxed, in fact, as the Tahiti entered the bay, and later as the Janie Seddon approached the wharf, he might have been nursing a degree of anxiety, unsure as to the reception he would receive. His name was Cyril Brownlie, and he was NZ’s biggest forward of the period - and his brother Maurice was the best[4]. Both were at the heart of the dominant Hawke’s Bay team of the early-1920s. A third sibling, Laurie had also represented Hawke’s Bay and NZ (once), but his career was cut short by injury; whilst a fourth, Tony, lost his life in WWI’s campaign in the Middle-East in late-1917. The Brownlies of Wairoa were North Island rugby royalty, and as so often in NZ rugby history, these key forwards came from farming stock.

In his welcome speech, there was something else that the Harbour Board chief had said, “If there were any regrettable incidents on tour, we know that you were not to blame”. Later, in various other speeches and press interviews, more references were made to a ‘controversy’. Tour chief Dean was asked directly about it, and he said, “I am quite convinced that the referee made a mistake”.

The ‘incident’? The ‘controversy’? Against England, in the opening minutes of the twenty-eighth and final match in the British Isles, Cyril Brownlie had been sent off, or, in pre-war parlance, he had been ‘ordered from the field of play’. Brownlie was the first man to be dismissed in the history of international rugby football.

As will be discussed, history tells us that Dean’s assertion was probably correct, and the referee, a Welshman by the name of Albert Freethy, had indeed made a mistake. One that had earned both him and Brownlie a certain unwelcome notoriety, however, in fact, for the record, Brownlie was not quite the first rugby union international to be sent from the field. In early-1923, an Australian forward called Ted Greatorex was dismissed when representing New South Wales against NZ, and in 1967, three years after Greatorex’s death, NSW’s matches were upgraded to international status. Then, in May 1924 at the Paris Olympic Games, the USA vs Romania rugby game saw the former’s Ed Turkington dismissed for a retaliatory punch. However, Brownlie’s sending off was the first in a full international match between the founding ‘board countries’[5] - and this was why it mattered more, much more, than Turkington’s did. His sending off had rocked the establishment - the heir to the British throne attempted to intercede - and society itself.

If Cyril Brownlie did feel uncomfortable and uncertain of his reception as he disembarked at the quayside, he was soon reassured of his countrymen’s favour. The Star noted, “The popularity of Cyril Brownlie was evidenced by a call for ‘three cheers’ (for him)….this showed in no mistakeable manner the feelings of the NZ public regarding the incident which happened in the English match”[6]. These sentiments were entirely genuine, but Cyril Brownlie’s name was still attached to an undesirable incident, one that had received the broadest public mention and one that merited official words at the very highest levels. It remained an unwanted label, and constituted a minor degree of shame that Brownlie would have to negotiate for the remainder of his life, which ended in 1954.

These days, our lives are full, if not frenetic. We are assailed with so much information that we cannot possibly absorb in full the vast majority of what goes on. A hundred years ago though, things were different. In the 1920s, individuals had home, family, work and church. Their leisure-time interests were not broad, and people had plenty of room in their heads for news and were almost certainly grateful for any diversions that major socio-political and sporting events created in their simple lives. If such involved a shock or a ‘scandal’, then so much the better, for discussion of it might sustain a community for a week.

At all levels of society sport, and international sports tours in particular held substantial interest, and if such a jamboree touched one’s own town, then it was probably second only to a royal visit. It is fortunate that one of the All Black forwards, Read Masters, kept a diary of his tour, and in 1928 it was published[7] - and one speculates that Masters may have invented a genre of literature. This document offers proof of the scale of the whole enterprise, and how the public in both countries were emotionally invested in it. Wherever they went, the touring All Blacks were lavishly entertained by civic authorities, by businesses and by the aristocracy and establishment; and they were also feted with great charm and enthusiasm by ordinary people.

The 1924 ‘Invincible’ All Blacks - with the Brownlie brothers standing directly behind the Tour Manager

Amongst the highlights of the tour, they would attend a point-to-point race meeting at Totnes, tour the battleship HMS Royal Sovereign at Devonport and HMS Victory at Portsmouth, visit the cathedrals at Wells and Canterbury, enjoy a number of castles, attend the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley and a ship-launching on the Tyne, tour the Lake District, visit the Guinness brewery in Dublin, march in the Armistice Day parade in Whitehall, dine at Cambridge and Oxford colleges, enjoy a sight-seeing flight over London, spend at day at the Palace of Westminster, walk the turf of Rugby School and meet King George V. The events of the tour must’ve been wondrous for most of the New Zealanders - especially the youngest, 19yr old George Nepia, who would play in every game on tour and thrill all with his play. In turn, the 1924 All Blacks left their mark on the game of rugby.

Just as their 1905 predecessors had done, having arrived at Plymouth, for the first two weeks of the tour, the 1924 party trained and prepared at Newton Abbott, Devon. Masters described the welcome given to the party when they arrived, “A vast crowd had gathered to welcome us…..flags were flying from nearly every house…streamers and bunting in profusion across the roadway…..their warmth and sincerity will never be forgotten as long as we live”. It is somewhat touching to note that the bonhomie of the British public and the generosity of its wealthy citizens and organisations is a common theme throughout Masters’s book. The only citizens who did not enjoy their company were the thirty players who, each week, attempted to stop the All Black juggernaut.

It should be noted that Britain was still significantly haunted by the losses of WWI but was beginning to come to terms with this blackest of periods. In 1920, there was a combined service for the interment of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey and for the inauguration of the Cenotaph. The following year saw the adoption of the poppy as a symbol of remembrance, and the establishment of the Royal British Legion. In the years that immediately followed, war memorials emerged in towns and villages across the nation, and the cemeteries for war graves appeared across the Channel in the form that we know them today.

Very slowly but surely, the sombreness dissipated as the return of normality allowed sport to resume, and for the spread of cheer and better spirit. The All Blacks’s tour would play a part in this.

In late-1920, after a resurrected but disjointed County Championship, England sent its cricketers to Australia for the first time since 1911, and the following summer the Australians visited British shores. In terms of rugby, the situation was slightly different, for people had been able to watch the sport during the war[8]. Matches between the servicemen of the ‘Mother Country’ and the ‘Dominions’ were very popular, and they culiminated in a ‘Victory series’, the King’s Cup inter-services competition of 1919. Naturally, it was won by the New Zealanders. Weeks later, the Five Nations championship resumed on New Year’s Day 1920. It was ultimately won by Wales on points difference, but in the seasons that followed, 1921-24, England’s record was very strong. When NZ arrived at Twickenham, England had not been beaten for two years, and indeed, not at all at home since 1909.

That is not to say though that the England players had not tasted defeat at international level. In summer 1924, the ‘British Team’ that toured South Africa, with little success. One of the tourists was the very athletic but somewhat pugnacious Gloucester forward Tom Voyce. The team did not return home until 13th October, and so he missed Gloucestershire’s match against the tourists, but played a prominent role in the international.

The New Zealanders had also played South Africa. In 1921, the South Africans who had not lost a series for over twenty years made their first tour to NZ, and it was billed as the unofficial ‘world championship’ contest. The three-test series was shared, but the tour was not without controversy, especially the game against the NZ Maori in Napier, which will be discussed later.

Most relevantly to this piece though was the consistent rough treatment the tourists received on the field of play. Just three days before the first Test, the South Africans went to Dunedin to play Otago. There is insufficient proof to state that the home side had wilfully set out to injure or intimidate members of the touring party prior to the Test, but after a torrid first half, a full-on brawl erupted just minutes after the second had commenced. At this point, SA’s captain, the splendid back-rower W.H. ‘Boy’ Morkel[9] threatened to take his players off the field if the rough play was not discontinued[10]. If there was no evidence of a premeditated arrangement to rough the tourists up, there was clear evidence of the tribal passion that New Zealanders had for both the game of rugby, and for their nation. NZ won the very first encounter between the two sides, but while impressed with the play on the park, parts of the local press were unimpressed with the conduct of the crowd. The New Zealand Truth reported, “…unseemly hooting and jeering….(deemed)…inhospitable and offensive…the barracking was rude and rough.”. It seems that - post-WWI - the locals directed abuse at the South Africans over their Germanic heritage, “In this country it is no compliment to be called a Hun, and yet members of the visiting team were stigmatised as Huns”. Clearly, the passion that New Zealanders had for rugby was closely tied to national jingoism. This element is still important to this day.

Back to the British Isles in 1924, where the NZ tourists would be treated most hospitably and with great generosity. History relates that the 1924 tour was enormously popular. From Camborne to Carlisle they would play in front of nearly 700,000 people, with crowds averaging 25,000. The All Blacks rewarded them with sharp-handling, fluent running rugby and physical defence. They kept the opposition scoreless on twelve occasions, and only three teams scored two tries against them. The ultimate points tally was 654 for with 98 against.

As alluded too, this was all achieved in style too, in 1955, renowned sports journalist and personality Wilf Wooller[11] - who we shall meet again - collaborated on a book with his esteemed journalistic colleague J.B.G. Thomas, who was writing under a pseudonym. Titled Fifty Years of the All Blacks 1905-54, the book detailed every game that NZ had played in Britain and Ireland until that point. A section of it asked a simple question - ‘What was the secret of their success?’ - and it was answered in terms that fans of NZ rugby might easily relate to 70yrs later:

“The short answer to this question is undoubtedly team work of the highest order allied to a high standard of physical fitness, determination, speed and intensive backing up. A feature of the tour was the piling up of points in the closing stages of many of their engagements. The forwards were tall and heavy, yet their size seemed in no way to impair their mobility. Close hand-to-hand passing amongst members of the pack was a form of attack to which most of their opponents had no effective answer. Always there was one or more colleagues within a yard or so of the tackled or half-tackled All Black when they were launching an attack. Even in the act of falling they contrived to pass, and pass accurately, so that the movement was carried on”.

They also played rugby, with a structure that was quite different to that of the home teams, John Griffiths relates[12]:

“Until the 1930s, the All Blacks packed down in a diamond formation at the scrums. There were two hookers upfront who swung their feet inwards to kick rather than heel the put-in back through a scrum that was backed by three second-row men and locked by two men in the back-row……under this arrangement, a scrum-half to put the ball in and an eighth man or ‘rover’, who used to crouch behind the forwards awaiting the heel, were deployed. In Britain, the norm was to pack down with three men in the front-row”.

If the seven NZ forwards could hold the British eight, then - for a few seconds at least - an advantage of an additional man in the backline accrued, and, usually, the All Black backs were sufficiently swift and skilled to make it count. However, some teams would attempt to counter this by taking a step to the side at scrum-time, and so pack down two-against-two, leaving a spare front-row forward free to defend immediately.

On 2nd October, having conceded just three points in their first five matches, in their sixth - refereed by a Mr. Albert Freethy of Neath - the tourists came up against a very formidable Newport side, and 30,000 home supporters. They were led by Reg Edwards, a bald bulldog of a front-rower, and a butcher by trade. He was born in Pontypool, but had ten caps for England, and was well-known for his ‘robust’ play. At times he adopted this ‘step-to-the-side’ approach at scrum time, which apparently created no small amount of disturbance[13].

Read Masters credited Newport with “great vim”, and mentioned the toughness of this game, particularly in the forwards. Friend scored the first try against NZ on tour, and Newport led at half-time. Andrews scored another in the second period, and with only a minute or so to go, the home side were ahead. At this point, Newport failed to find touch, Maurice Brownlie fielded it and fed Svenson who raced in for the winning score.

The South Wales Argus reported, “Of course the New Zealanders had the lead of the Newport backs…..they were faster men, bigger and stronger…..clever with their speed and strength”. However, the overall assessment was that the All Blacks had been a little fortunate, “The feature of the game was undoubtedly the magnificent play of the Newport forwards. They showed tremendous dash……and they were always on the man……they ought never to have been beaten….the lesson of todays’ game is that it is possible to bustle and beat the All Blacks”. Doubtless, England’s captain, Wavell Wakefield would have taken notice, and may have conferred with Reg Edwards. We cannot know what was said on the field, and how the opposing players inter-acted, but it is possible that Edwards, had squared up to NZ and issued ‘predictions’ for the international.

Despite their brush with defeat, NZ’s quality and determination won through, and this ability to persevere and win tight games was to become a very common feature for the remainder of the twentieth century, during which, there is no question that New Zealand became the ‘emperors of rugby’. Only the most determinedly one-eyed South African would - or could - deny them that accolade, even though it took the All Blacks until 1996 to win a series over there. In the twenty-first century though, things have been slightly different. Even though NZ have won two world cups, South Africa have won the two most immediate. Whilst Australia’s record has diminished,[14] France, Ireland and England have shown themselves capable of beating New Zealand more regularly than they used to.

These days, the aura of invincibility is not as unshakeable as it was, but all told, NZ dominated the twentieth century and is still the team that other nations measure themselves against. Probably, it was the 1924-5 tour that saw the origins of that aura, but on the morning of Saturday 3rd January 1925 it was not fully established.

Reeling from the ruination of war, there had been no international games in 1919[15], but the Five Nations had been resurrected in 1920, and, of their twenty post-WWI matches, England had lost just two - both in Cardiff. Further, they had lost at home just once at Twickenham, to South Africa in 1913. So, as for the very first time England welcomed NZ to Twickenham, under Wakefield’s captaincy they were the dominant force in Europe. That said, due to tourist’s splendid record in the shires not too many people expected a victory over their strong forwards and quicksilver backs, but it was generally believed that England could ‘run them close’. Both sides where ‘highly motivated’, the unbeaten record was a significant spur for both.

By the evening of Saturday 3rd January 1925, people were sure they had seen the two best teams in the world, with the tourists establishing themselves as genuine champions. NZ went on to triumph at Twickenham, having played with 14 men for well over an hour, because referee Albert Freethy had sent Cyril Brownlie for that ‘early bath’. It was a very early bath, because fewer than 10 minutes earlier, Brownlie had been shaking hands with the Prince of Wales and doing the haka.

The opening clashes of the game were very rough and contained what Read Masters termed “excessive unpleasantness”, with a number of arm-flailing melées, doubtless with Reg Edwards and Tom Voyce were involved and the tourists met fire with fire. Masters recorded that, “Thrice the referee issued a general warning to both packs”. Afterwards, Freethy stated that having given a general warning to both sides to ameliorate the ‘rough stuff’, he saw Cyril Brownlie “deliberately kick” a player on the ground and so he was sent from the field of play. On the pitch, Brownlie and his team-mates protested his innocence, and it took nearly two minutes for him to trudge off. It was said that NZ skipper Richardson twice asked his opposite number to intervene, but Wakefield claimed that due to his headgear, he did not fully comprehend. Afterwards, Wakefield said that it would have been wrong to challenge the referee. It was also the case that at half-time, the onlooking Prince of Wales sent a request that Brownlie be recalled, but he was advised that this was ‘impossible’.

Later, tour manager Stan Dean disputed this vehemently, and later told how, “I went to the referee after the match to ask him what happened, he said, ‘I have made a statement to the press’…I then went to every English forward - they had an idea that Brownlie must have punched a man. I asked them if anybody was kicked on the ground. Not one remembered such a thing. I was watching closely and I saw everything. I say deliberately that the referee was wrong. There was no man on the ground. If we had not lost Brownlie when we did, we would have beaten England by 40 points”.

Film cameras were present that day, but they were there principally to document the occasion and not record the action - which would have been technically quite scratchy anyway. Footage only shows the emergence of the teams onto the field, the team photographs, the royal greetings, the All Black’s haka and a few random clips of action. If any footage of the prominent incident exists, it could not be found.

The great hush that fell upon the 60,000 crowd would have immediately communicated to those on the pitch the enormity of what had just transpired. Read Masters called it a “weird silence”. It was also reported, “…in utter silence, he crossed the Twickenham pitch, the loneliest man in the world”. The Daily Telegraph stated, “C. Brownlie separated himself from the group in obedience to the referee’s gesture, and walked dejectedly, head down, 50 yards to the exit under the box in which were the Prince of Wales and the Prime Minister, Mr. Baldwin. The crowd, unaware of the nature of the offence, felt it marred the glory of a triumphal tour at its climax, and later showed exaggerated generosity in cheering the New Zealander’s prowess”.

The Daily Express explained, “Had not firm action been taken the game would undoubtedly have degenerated into one of the roughest ever played. It would be unfair to suppose that Brownlie was the only offender. It was his misfortune to catch the referee’s eye twice”.

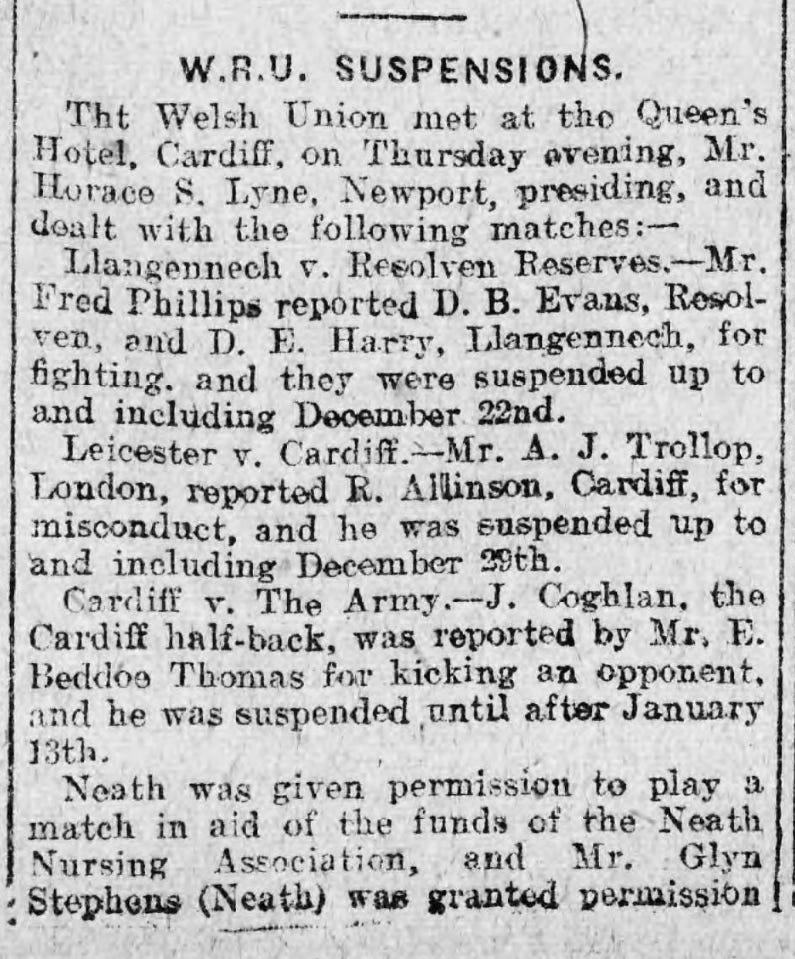

Being sent off was not entirely rare, but being so in a big fixture was not at all a common occurrence, and it was something that engaged emotions of those watching and was always reported in the press.

For example, in mid-December 1919, the Cambrian Dailyreported the expulsion of a home side player in the Cardiff vs Army fixture, “During a scramble in the game the referee (Mr. Beddoe Thomas, Newport) suddenly blew a long blast on his whistle and separated the players. Then to the astonishment of the spectators, he ordered Johnny Coghlan off the field. The crowd booed lustily and cheered Coghlan as he left. When the encounter terminated the crowd surged toward the referee, and Wick Powell the Cardiff skipper formed his twelve colleagues into a body guard toward the referee, and, with a booing mob kept in place by the police, the referee….reached his dressing-room in safety.”[16]

As can be seen, the newspapers even reported the outcomes of related disciplinary hearings - an additional public shame.

The New Zealanders were all celebrities, and their fixtures were not just big, they were very big. One of them being ordered from the field against county opponents would have been back-page headline news, and so a dismissal in an international would have been a sensation, and of course, a humiliation. However, on that occasion, Cyril Brownlie’s shame served only to inspire the New Zealand players, particularly his brother Maurice, who played like the colossus he was to win the match, and also to fix his family’s name. He scored a try after bullocking through three or four Englishmen, with another clinging onto him, “the most determined try” Read Masters “had ever seen”. New Zealand won 17-11.

Perhaps Albert Freethy’s decision was correct, but his justification wrong. Almost certainly, there was no ‘kicking’. To this day, the England player who was supposedly kicked has never been identified. Over thirty years after the event, five years after Brownlie’s death, the well-known NZ author (Sir) Terry McLean published a book[17] in which he quoted the words of Jim Brough the England full-back, who was making his debut that day. He said, “The England team did not think that Brownlie kicked anybody. England was keyed up to beat the All Blacks and went flat out from the start. Edwards was a tough guy. A bit free with his fists, and others in our forwards were tough too. We believed that Freethy was so determined to assert control that he decided the only way to do it was by sending Brownlie off”.

Material compiled by NZ’s very own Bill McLaren, Keith Quinn[18], quotes the 1905 All Black journalist E.E. Booth stating that Freethy had ‘lost it’, “There is every reason to suppose that he (Freethy) was considerably over-wrought and overly excited about the fiery aspect of the opening play”. This claim is considered unlikely for Freethy was the Nigel Owens of his day. He was well-known as a coach and was as experienced and respected as any referee active at that time. He was the first WRU referee to be invited to control a club match in England (1920), he had officiated in six Varsity matches, the Paris Olympic rugby final of 1924, and all told, between 1924 and 1931, he blew the whistle in at least sixteen internationals. One suggests that there was but a small prospect of him being over-awed. After all, he had already presided over five of the All Blacks’ tour games, including the Test match against Ireland and the rough and intense tumble of the Newport match. It is highly likely that Freethy knew full well what would eventuate at Twickenham, and one rather suspects that having given the players, of both sides, three collective warnings to conform he sent Brownlie off in response to his warnings being ignored.

One unknown journalist’s sentence typifies the ameliorating diplomatic niceties of the period, “Writers remark that any roughness in play was due to the exuberance in exciting moments, and there is evident desire to relegate to oblivion the painful incident…”. The English authorities went into overdrive, seeking to simultaneously protect the dignity of the game and its ‘sole arbiters’, and also to safeguard important imperial relations. There was little chance of the matter being ‘relegated’ though. The fact is, the Brownlie incident, or perhaps it might be called the ‘Freethy incident’, procured hundreds of thousands, if not millions of conversations and generated inch-after-inch of newspaper coverage. It was an unhappy start to the new year for all except the newspaper proprietors.

Also making his international debut in the infamous match was Durham and Oxford University prop Ronnie Hillard, who had already played the All Blacks twice on tour. So disillusioned was he with the violence of the opening exchanges that day that he stated that he did not wish to play international rugby again - and didn’t.

Another man who never played for England again was Reg Edwards. Terry McLean observed that Freethy reported Edwards to the RFU, and it is reasonable to say that it was highly likely that Edwards - and Voyce too - had been front-and-centre of at least two of the brawls that erupted in the opening minutes of the match.

Doubtless, the RFU, ‘deeply regretted’ the whole incident and put the damage done down to the ‘effervescence of the occasion’. They then did what the establishment always does, it supported the referee and in the ‘spirit of the game’, proceeded to make one of their own players a scapegoat. Not the captain though, the Corinthian Wavell Wakefield[19], nor of course the illustrious Tom Voyce[20], but one of the expendable working-class ‘brutes’ who was close to the end of his career anyway.

Ten years later, in 1934, the British sporting establishment pulled the same trick on Harold Larwood, after the infamous Ashes series of 1933. The Marylebone Cricket Club instructed Larwood to write a letter of apology to the Australian Cricket Board for obeying his skipper’s instructions to bowl bodyline. Quite correctly, Larwood refused, and so, his career in international cricket was terminated at the age of 29yrs.

If he suffered, and doubtless he did inwardly, Cyril Brownlie’s rugby career did not. The following weekend he lined up to play a ‘Parisian’ XV at the Stade de Colombes, and then again against France in Toulouse - but this was to be his third and final cap. Whilst he toured Australia in 1926, and South Africa in 1928 - under Maurice’s captaincy - he did not play in the test matches. He ceased playing in 1930 and went back to his farm, where died aged 58yrs in May 1954, sadly, not long enough to see his 8yr old son Jeff play for Hawke’s Bay.

According to McLean[21], Maurice Brownlie was ‘keenly sensitive about the incident but harboured no grudge against Freethy,’stating, ‘the best referee I ever played under was Albert Freethy of Wales; he was outstanding. And he was quite right about my brother, Cyril. Cyril did punch Voyce, though this was a retaliatory blow after Voyce had belted him’.

As mentioned, both Cyril and Maurice were WWI veterans of the campaign in Palestine and had lost their brother Tony there. One suspects that, however great it was, they would have been able to put a sporting embarrassment into perspective. Nevertheless, to be the first man ordered from an international rugby field was (is) a weighty epithet and constituted a small stain on the family name. This is something that nobody playing international rugby in the twenty-first century could possibly comprehend, for a player getting sent off is surely now more common than scoring a hat-trick of tries

McLean added that when the brothers returned from the tour, “no one, unless invited, ever spoke about it to any member of the Brownlie family”.

Maurice too died young in 1957. Neither brother lived long enough to see another player sent off in an international, which these days is more common than seeing players score hat-tricks of tries. That must’ve a minor burden for Cyril to carry.

Only Freethy himself will have known if he was entirely comfortable with the decision - but nobody in NZ was. The Kiwi public forgave Cyril Brownlie, but not the referee. Freethy had also been a decent cricketer, and after rugby, he became a member of Glamorganshire’s committee. In 1937, he was in a Swansea bar, and introduced himself to, “….a New Zealand cricketer who had also been an outstanding rugby player”[22]. Unfortunately, the unnamed individual proceeded to treat Freethy with hostility. Similarly, in 1953, in Porthcawl, when a call for an introduction was made, two members of the touring 1953-4 All Black squad declined to shake his hand.

One strongly suspects that from 3rd January 1925, until his death on 17th July 1966, in his wistful private moments, Albert Freethy probably wished that he had dismissed two players - one from each side. Given that he did not, perhaps it might have been better for Wakefield to have voluntarily reduced his side to fourteen men.