Canterbury St Lawrence Ground

Credit: Kent County Cricket Club

When April with his showers sweet with fruit

The drought of March has pierced unto the root

And bathed each vein with liquor that has power

To generate therein and sire the flower;

When Zephyr also has, with his sweet breath,

Quickened again, in every holt and heath,

The tender shoots and buds, and the young sun

Into the Ram one half his course has run,

And many little birds make melody

That sleep through all the night with open eye

(So Nature pricks them on to ramp and rage)-

Then do folk long to go on pilgrimage,

And palmers to go seeking out strange strands,

To distant shrines well known in sundry lands.

As Geoffrey Chaucer so sweetly described nearly 650yrs ago - when April comes around people undertake sacred excursions, sometimes at great length, to pay homage to that which they hold dear.

Whilst the vast majority of us no longer worship - at any time of year - before the shrines of saints and tombs of kings at places like Canterbury, Durham or Worcester; quite a few people do still make their way to those cities - and a good few others - to kneel before the divinity of the blessed St Salix and the polished Duke of Leather.

They may need a thermos of hot tea, a thick jumper, or even a stout coat at first, but up and down the country, thousands of cricket fans will be greatly looking forward to sitting amidst the brilliant white fringes of the pristinely manicured green pancakes of the shires.

On Friday 4th April, extant since 1890, the County Championship1 of English and Welsh cricket will get underway again. At the grounds, given decent weather, whilst the terrace crowds will be sparse, the members’ pavilions and nearby seating may see correspondingly cheering turn-outs2.

However, until the summer holidays - and a different game - materialise, these shallow bowls will not host the crowds that gathered in the 1970s, never mind the multitudes of 40yrs before that. Yet, for a solid core of supporters, attending County Cricket matches remains a life-affirming ritual of retirement. It is a trap-door to their youth. As I write, they will be confirming their routes to Chelmsford and Chesterfield, Hove and Headingley and Taunton and Tunbridge Wells. They will check their car tyres and top up the oil; the wife’s sister in Northampton will be asked if it is okay to drop by and their sun-hat, notebook and binoculars will be placed - alongside the biscuits and corned-beef sandwiches - into the same thirty-year old bag that was present when Warwickshire won the cup at Lord’s in 1989.

A ‘Stout Yeoman of England Showing the Mettle of His Posture’ - Lord’s, 23rd April 1975 - His Kind Survives, Just

Credit: Getty Images

Regrettably, these loyal - most are longstanding members of their county cricket clubs - fans have been treated poorly. They have been banished to the margins. The format of cricket that they care most about is now played in the chilly months of the spring and autumn - the prime, halcyon months of summer are reserved for that different game. Our stout yeomen belong to the wrong demographics, and the marketing men care nothing for them - or their game3.

Given the changes that cricket has seen in recent years, and the mercenary attitudes that currently prevail in our nation’s various sporting establishments, the meaningful continuance of the County Championship probably cannot be considered a certainty for too much longer.

Pause for a moment though, perhaps this is an unfair, unrealistic and pessimistic view? Has not the cricket fraternity always grumbled and been split by controversy? Over the past century, predictions of the ‘death of cricket’ been made with almost ceaseless regularity.

In 1901, at the MCC’s AGM4 one of the great Victorian Corinthian sportsmen Alfred Lyttleton5 aired his opinion of the proposed change to the LBW law, “I do not think I have ever heard anybody dispute that the game is made more tame and monotonous than it ever was…..what wonder is it therefore that other and inferior games like golf entice away the disappointed cricketer, and satisfy him with the sedater joys that the belong to that game?”6.

In 1933, a Captain W.A. Powell of Kent CCC published, an independent report on the matter of The Future of Cricket, The Cause of its Decline and a Suggested Remedy. We can be almost positive that for nearly 150yrs, many other individuals - whether they published them or not - will have constructed their own plans to ‘save cricket’. It’s a very British thing to do.

More formally, in 1956 the influential think tank Politics and Economic Planning published a report entitled The Cricket Industry which forecast a none too positive future for the game7. Concomitantly, the MCC set-up another committee. In fact, between 1937’s Findlay Commission and the Rait-Kerr Committee which reported in 1962 there were at least five MCC-appointed committees instructed to examine and report on the strengths, weaknesses and structure of the game.

Eventually, at least some of these committees’ recommendations were adopted (we shall not discuss those that were not!) and mostly proved constructive. In rough chronological order they were:

recognition of the importance of cricket to British culture; greatly boosting morale, in 1943, 250,000 attended 47 wartime cricket matches and 170,000 in 1944. In 1941, MCC official Harry Altham noted, “…..the Long Room was stripped bare…..but, one felt that somehow it would take more than totalitarian war to put an end to cricket”8.

the necessity of establishing a national youth coaching strategy; MCC Treasurer Harry Altham, with full support from 1949 MCC President HRH Prince Philip - himself in the process of creating his DoE scheme - established the Youth Cricket Association and the English School Cricket Association.

the need to improve gate receipts; in the post-war boom year 1947 over 2m paying customers passed through the gates to watch the County Championship. By 1961, this figure had fallen to 969,382 and then to 719,661 in 1963.

the need for more energy and excitement in the county game; necessary because professionals - paid by results - took the game too seriously and adopted negative tactics to avoid losing. “Committees should encourage the captains and players…..that cricket should beeper, quick and full of action”, wrote MMC Secretary Colonel Rowen Rait Kerr in Wisden in 1951.

the need to end the distinction between amateurs and professionals; it was considered essential to preserve the care-free spirit of the amateur ‘gentlemen’ to counter-act those hard-bitten professional attitudes. However, post-war, such wealthy self-sufficient men became rare. The MCC Report of 1957 noted, “….the wish to preserve in first-class cricket the leadership and general approach to the game traditionally associated with the Amateur player,”..….but recognised that in the modern world most amateurs can no longer afford to play “entirely at their own expense”. The Committee rejected abolishing the amateur/professional distinction and expressed concern at the “over liberal interpretation of the word expenses”. Nevertheless, the distinction was abolished for the 1963 season.

the need for covered pitches; an on-off-maybe saga that lasted over one hundred years was resolved in 1979, when total, indefinite covering was allowed for Tests - and in 1982 for first-class games.

the benefit of allowing overseas players into County Cricket; until the late-1920s, only a small handful of professionals in league cricket had been overseas players - from Australia and South Africa; in 1929 following West Indies first full Test tour of England, the outstanding all-rounder Learie Constantine was signed to play for Nelson. Soon afterwards, Edwin St Hill was with Lowerhouse, then Haslingden signed the great Jamaican batsman George Headley and quick bowler Manny Martindale was playing for Burnley. After impressing in the 1933-34 Test series against England, Indian all-rounder Amar Singh was signed for Colne. In the 1930s, these ‘exotic’ players proved huge hits with club treasurers because gates increased - the likes of Constantine and Headley were the Salah and Haarland of 1930s cricket. People wanted to see them. After WWII, the numbers of overseas players - from all nations, even Ceylon’s Stanley Jayasinghe - in the Lancashire League and elsewhere, increased exponentially. County Cricket would have little choice but to admit them to the first-class game. Indeed, this happened in two stages: first, by 1955 there were about 20 overseas players who had qualified as ‘residents’ - 5yr qualification - and this number expanded; then, for the 1968 season the counties voted to allow the registration of one additional non-resident overseas player.

the introduction of one-day limited-over cricket; a One Day Cup (ODC) was inaugurated in 1963 as 'The First-Class Counties Knock-out Competition for The Gillette Cup’9. In 1969 the John Player League was introduced10. Then in 1972, the Benson & Hedges Cup was added11. Writing in the Daily Mirror on the first Gillette Cup final, Peter Wilson proclaimed, “Lord’s, the temple of tradition, could be transformed…..into a reasonable replica of Wembley……this triumphal sporting experiment may not have been cricket to the purists, but by golly it was just the stuff the doctor ordered”12.

Sussex Captain Ted Dexter and His team with the Inaugural Gillette Cup - Lord’s, 7th September 1963

Credit: ESPN

The 1960s saw radical changes in all spheres of life, and cricket was not exempted. In 1974, that polymathic sporting journalist Gordon Ross wrote a piece for Wisden in which he asserted, “No decade, in the whole history of the game of cricket, has produced so much fundamental change as that which began in 1963…..”. The 1970s would see even more.

Yet these great changes only procured more debate. Nobody who followed the game in the 1970s and 1980s would deny that the effects of short-form cricket on the skills of long-form cricketers was a regular theme in cricket columns and with TV pundits. Such issues dragged on and on: in 1963 there were not enough overseas players in English cricket, but by 1983 there were too many. In the same period, covered pitches were essential to promote better batting, but then people moaned that doing such had killed the art of leg-spin. County Championship fixtures were re-structured13 - but there were either still too many or insufficient games.

By the 1990s, there were loud and protracted arguments about just one issue: ‘why were England so poor’? Dumped out of their own 1999 World Cup tournament and bottom of the Test rankings as they were. After 30yrs of dire results, capricious selection and indifferent management, the authorities decided to abandon tradition, and centrally contracted England’s premier players. In essence, the national authorities, not the counties, would pay and control them.

Results in Test cricket unequivocally improved, but the lustre of County Cricket was dulled quite substantially. If a county had ENG players on their books, supporters saw precious little of them after early-May.

So began the long-term, organic restructuring of domestic cricket. By 2010, the innovations of the 1960s would all be swept away, and probably rightly so. The two 50-over cup competitions never produced a World Cup winning side. Whilst one does miss the 40-over Sunday league, it must be admitted that it served no purpose other than to thwart the puritans of the Lord’s Day Observance Society, take good gate money and sell lots of beer - or cider at Taunton (where the crowd knew all the words to “Somerset La-La-La”) - on an extended weekend. It was a lot of fun though.

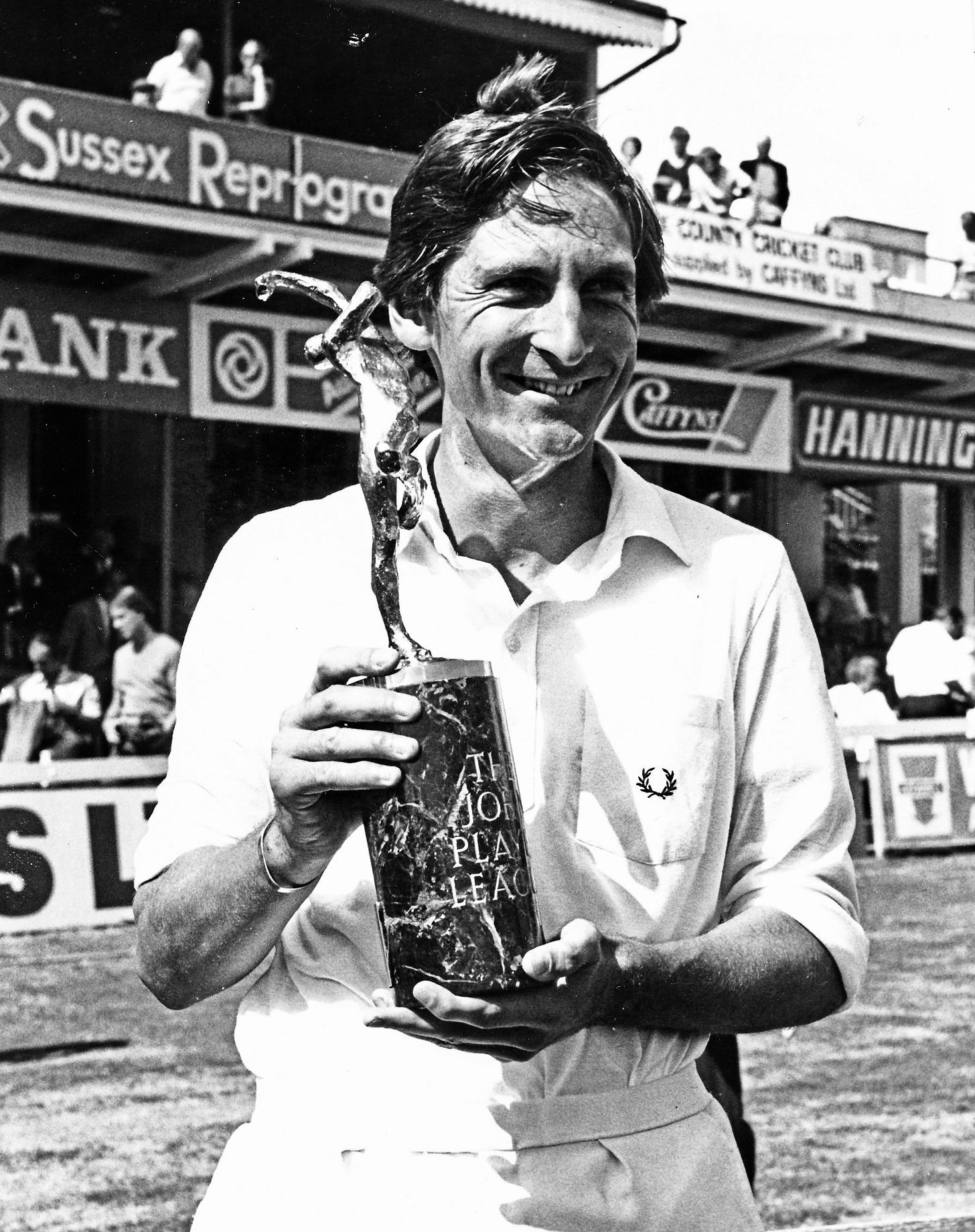

Sussex Skipper John Barclay with the John Player League Trophy - 1982

Credit: Sussex Cricket Museum

Today’s cricketers receive handsome salaries, abundant media profiles and greatl popular acclaim, but only some of them. Outside contracted England players -who play multi-format for England and franchises - the best rewards are reserved for the ‘thrash merchants’. These are the men who bat for 75-balls a game (if they’re lucky, but usually only 10-20) and/or bowl 24-balls and evening.

Yes, an evening for increasingly, cricket is now a game that lasts for four hours under floodlights. It is called ‘T20’ and from Benglaru to Birmingham it has grown into a mammoth enterprise. It is certainly a product that people enjoy: large stadia are filled with smiling families, girlfriends beg their boyfriends to ‘take them to the cricket’ and corporate boxes sell like hot-cakes - and it’s all done after work. Genius really.

The players love it of course, their hourly rate will be astronomical, and given the shelter-skelter nature of the game there is not much accountability for failure to deliver.

All that said, a good degree of the game’s grace, dignity and soul has been forsaken, exchanged for sensation, swift gratification and for emotions expressed outwardly. T20 is about the ‘whole stadium experience’ of a howling, jazzed-up, gladiatorial thrill-fest accompanied by deafening music and bellowed announcements. It’s about generating atmosphere and advertising - not the exquisite art of flight and stroke.

This is OK, there is certainly a place for T20. Resisting the concept would have been folly - akin to rejecting Kerry Packer in 1977; but, as long as T20 advocates accept that the purest, longest form of the game must have primacy, and be nurtured ad infinitum, the two variations can co-exist. One doubts that this will be so.

Crawley - Katich - Udal - Prittipaul - Mullally - Hampshire Hawks vs Sussex Sharks - First Ever T20 - 13-JUN-03

Credit: ESPN

So, here in the 2020s, the cricket authorities in England and Wales have decided to accommodate five formats, which are:

Red Ball

Test Cricket - 5-days, usually 6 tests, so in theory 30 days per summer.

County Cricket - 4-day games, allotted 4 rounds in April, 4 rounds in May, one round June/July, 1 round in July, 1 round July/August and 3 rounds in September14.

White Ball

One Day Cup - 50-overs, two groups of 9 - 8 matches, plus QF & SF - in August, with the final in late-September

T20 Cricket - 20-overs, 14 fixtures for each county from late-May to mid-July with finals in early-mid-September

……..and then there is The Hundred:

Hundred Balls - throughout August, 8 regional franchises (with both male and female teams) each based at a Test ground playing double-headers of a bastardised format that is fast, furious and facile. From a purist’s point-of-view The Hundred is crass, meretricious, Mephistophelian garbage. Probably, it would not survive were it not for the ludicrous ersatz hype and large amounts of money thrown at it. This questionable sport adorns cricket like a pimp’s hat. Its television rights expire in 2028, what will happen at that point is hard to predict, much like rugby union, cricket is run by venal knaves.

The Hundred Winners 2022 - but Are Cricket Fans Going to Be Losers?

Credit: Sky Sport

One can concede that The Hundred’s male-female double-header games the tournament has been good for women’s cricket15, but it’s otherwise been a circus.

Earlier in the winter, the eight franchises were sold, in whole or in part to various overseas investment bodies for approaching £600m16.

Apparently, the ECB and counties will ‘invest’ much of this money in the British grass-roots game. One doubts there will be much classical coaching though. The product will be youngsters with ambitions to become highly paid white ball ‘thrash merchants’; and they will be more than happy to take the money and leave their counties for the commercial franchises..….and another bit of our cultural heritage will be denuded.

It’s already happening. One of the eight teams is Welsh Fire, based in Cardiff and supposedly selects from Glamorgan, Somerset and Gloucestershire players - yet Yorkshire’s Jonny Bairstow and Warwickshire’s Chris Woakes play for Fire; Kent’s Zak Crawley and Essex’s Dan Lawrence play for the Northern Superchargers, a Durham and Yorkshire based team. The are numerous other examples.

As evidenced by the fact that so many tickets for games are given away or sold cheaply, The Hundred exists only for television. Its PR jamboree would have people believe that it is the greatest form of the game ever; but it is cheap and nasty, and represents the lack of acuity and integrity that abounds in all sport these days.

There are signs that a lot of people have already turned off The Hundred. Sky TV data tells us that between 2021 and 2024, the men’s version lost 54% of viewers (falling to 43% when shared with the BBC), whereas the women’s version lost 37% (33% with the BBC). As stated, live attendances are largely sustained with cheap and free tickets, so it is clear that The Hundred is not an attractive proposition, it cannot hold peoples’ attention, never mind earn their affection. So why did eight parties pay £600m for their stakes in it? Some believe that within a few years, The Hundred will morph into the prime T20 competition17.

As mentioned, County Cricket has been pushed aside. The Hundred has procured the partial disownment of the One Day Cup, for none of the top players play in the 50-over tournament. In effect, it has become a second XI competition. The Hundred has also had an effect on the T20 ‘Blast’, with lower attendances a reality18.

So that is the situation of English cricket in the 2020s. Essentially, the real domestic game is contested in the chilly months that bookend the 6-month season, with 50-over cricket - which, these days, most purists do cherish - not played by the top players, and T20 under threat.

There will be medium and long-term consequences for devoting a large proportion of the season to vulgar, ‘It’s A Knock-out’ tomfoolery. The skills and mindsets required for long-format cricket will be impacted. The prospect of T20 replacing Test cricket may not be perceptible, but it is real. The sacred culture of cricket and its hinterland could be dissolved. Virtue displaced by vulgarity - like Banksy replacing Botticelli, or Miley Cyrus preferred to Mozart.

Some claim short format cricket has benefitted ENG’s Test cricket, citing the ‘success’ of ‘Baz Ball’19. Whilst there have indeed been some thrilling run chases and wonderful individual innings, in general this is a ludicrous statement, and anyone believing it would do well to examine ENG’s results in detail. In the past four years from 2021, they have won:

vs Australia - 2 from 6 Tests and no series

vs India - 4 from 14 Tests and no series

vs New Zealand - 5 from 10 Tests and one series

vs Pakistan - 4 from 5 Tests and one series

South Africa - 2 from 3 Tests and one series

Sri Lanka - 5 from 6 Tests and two series

West Indies - 3 from 6 Tests and one series

That is 25 Test wins from 45 matches, and six series wins from sixteen; and currently ENG stand fourth in the ICC Test world rankings20. In the ODI (50-over) rankings they are seventh, and third in the T20 list.

In terms of individual players, in Test cricket ENG has two batsmen and no bowlers in respective top-10s; for ODI there are no ENG players in either; for T20 it is one in each; and finally, and rather embarrassingly, Joe Root is ENG’s top ranked ‘all-rounder’ in Test cricket.

It seems that The Hundred, and the whole shenanigins of T20 (and IPL) has been a distraction. In 2019, ENG won the ODI World Cup; then The Hundred commenced in 2021. In the 2023 ODI WC, ENG failed miserably and didn’t even qualify for the knock-out stages, losing to Afghanistan along the way.

Coincidence?

In summary, I will not emulate Capt. W.A. Powell and outline a charter, or even a three-point plan, to ‘save the game’, but I will relay two poignant remarks from 70-80yrs ago.

In July 1956, in the midst of another general ‘future of the game’ debate, Sir Donald Bradman wrote to the Daily Telegraph with six suggestions as to the future of cricket. His final one was this: “It is dangerous and unhealthy to place cricket’s financial future in the hands of its ancillaries rather than its own inherent attractiveness for spectators”21.

David Lemon quoted the poet Stephen Spender’s comment about cricket during WWII, “Looking back now, it seems to me that in England, the war period was a little island of civilisation in our lives. Civilised values and activities acquired a kind of poignancy because they were part of what we were fighting for……”22.

Personally, long-format cricket represents civilisation and it must be preserved. There is certainly room for, 50-over cricket and T20, but The Hundred is unwelcome.