This piece is a long one for a ‘photo of the week’ feature, apologies. If not exactly enjoyable, I hope readers find it informative and worthwhile. The principal references are below.1

10th February 1971: Keisaburo Shimamoto (Newsweek), Henri Huet (Associated Press),

Larry Burrows (LIFE) and Kent Potter Board (United Press International) Board their Fatal Flight

Credit: Sergio Ortiz

On 10th February 1971, the world lost five brave photo-journalists, each one a different nationality: Larry Burrows - British; Henri Huet - French-Vietnamese; Keisaburo Shimamoto - Japanese; Kent Potter - American and Tu Vu - Vietnamese.

These days, to varying degrees, many of us have lost faith in the ‘mainstream media’ (MSM). Our principal television channels and newspapers - even the supposedly liberal conservative ones - seem to have surrendered their independence and impartiality to governmental, corporate and ‘philanthropic’ interests. Here in Britain, even the state broadcaster, the BBC, derives well over 30% of its income from outside the mandatory licence fee2. Inevitably, editorial ‘sovereignty’ gets sacrificed to commercial arrangements and the agendas of any donors. Similarly, with the consumption of hard copy newspapers in serious decline, publishing groups have also decided to accept supplementary funds with concomitant obligations towards ‘featured content’.

There’s another issue too. Competition from the truly independent commentators operating on social media platforms has proved a real threat to the viewing/reading figures and revenue streams of MSM. Consequently, they have a strong interest in supporting political attacks on their competition and seem content to demand regulation. Unequivocally, such behaviour means that de facto, the MSM is participating in the suppression of free speech. Not a good look.

If we accept the premise that the MSM is willing to do this, then it follows then that the reporters we see on the television news and the journalists whose newspaper columns we read will not be impartial. The ‘talking heads’ spout prepared scripts, whilst the columnists are bound by editorial instructions concerning which issues to emphasise, and which not to investigate and report on at all. How many in the MSM maintain the scope to think, investigate and report for themselves? Worse, once journalists eschew intellectual probity, then other values begin to fall away too3.

Sadly, we have reached a stage where if journalistic integrity were an animal it would be a Javan rhinoceros. More than in any other period, political powers and financial interests determine how the Fourth Estate operates. All rather worrying.

Exploring how this situation came into being would require a separate piece - one that this author is not really qualified to compose. This Stack is about history and nostalgia, and generally asserts that our existence was better in bygone times. Times when the creatives were possessed of free minds and times when courageous journalists were dedicated to discovering and publishing the truth.

This piece is about journalistic integrity and sacrifice. Today, exactly 54yrs ago those five photo-journalists died when the helicopter they were travelling in was shot down over Laos4 . They had all been covering the Vietnam War for some years, and on numerous occasions they had risked their lives to photograph the war and thus transport the truth to the readers of the world’s newspapers and periodicals.

With their courage, dedication and skills, such was the value of what these photo-journalists contributed to the public domain that each and every one of them merits the deepest respect. These men - and a few women5 - risked, and indeed forsook, their lives to document the consequences of the folly and callousness of politicians and generals. They also portrayed the bravery, stamina, struggles and humanity of the soldiers they photographed, and also the heartless brutalities inflicted upon civilians and their habitats. They had tremendous pride in their profession, they respected those they pointed their cameras at and were committed to the public’s right to know.

If servicemen were going to die or be maimed or psychologically damaged, and if great national treasure was expended in the process, then the people at home had to be shown the ‘when’, ‘where’ and ‘how’ of it all. The people at home (and in the wider world) also needed to be confronted with the ‘why’ and the ‘what for’ of the war-mongering policies that the governments instigated in their name.

Fallen Troopers of 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne - An Ninh - One of the First Actions of US Troops - 18-SEP-1965

Credit: Henri Huet

Whilst there was no freedom of the press in Communist countries, 50-60yrs ago in the West it used to be a bit different. It was accepted that however unpalatable (and ‘incovenient’) news might be, people could be presented with the facts of national and geo-politics generally, and of the Vietnam War (VW) specifically. Certainly, there were elements of censorship, but nothing that was ethically poisonous, even if journalists such as David Halberstam6 upset the establishment with criticism.

Supposedly instigated in the name of American democracy and expedited with Americans’ tax monies, journalists were expected to ask questions and demand answers about the war. It was crucial to record any negative elements of corruption, cruelty, crass incompetence and the appalling spoliation of ancient Vietnam. Similarly the positive aspects of servicemens’ duties: the friendship and teamwork, the courage and skills of corpsmen and surgeons, the calmness of front-line leaders and helicopter pilots and of course, the human qualities exhibited by men under pressure.

It was vital that the public knew the truth. Unlike today, public opinion mattered. Presented with the whole picture, voters could make choices. Politicians were accountable for their policies and decisions and the photo-journalism of Vietnam charged the public mood, which forced changes in policy and cost politicians their offices.

President Lyndon Johnson and Defence Secretary Robert McNamara at a Meeting - 7th February 1968

Credit: Yoichi Okamoto

On 31st March, just seven weeks after the above photograph was taken, Johnson announced two things: firstly, a change in war strategy; and secondly, that he would not seek re-election as president. McNamara had already announced his departure.

Photo-journalism mattered. Whilst the written word, and the spoken word mattered too, photographic images seared into peoples’ minds. As is often said, ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’. If a regular news article/report contained 3,000 words, then photographers would have written small libraries - Burrows and Huet in particular.

If their driving forces as professionals were clear and constant, what of their personal motivations? One can only speculate, perhaps: like the restless they wanted the adventure; like the slightly mad they relished adrenaline-rushed; like the troubled they wanted to prove something; like the lonely they enjoyed the camaraderie and like the bloody-minded they were determined to tell the stories to spite someone or something.

This piece is written in deep appreciation of limitless fortitude and splendid work of this splendid species of men. This includes the South Vietnamese photographers, who, apart from the legendary Dang Van Phuoc and Pulitzer-winning Nick Ut have remained largely anonymous - to all except the Vietnamese anyway.

Before going further, we should note that these men were in Vietnam by choice, but there were some who were there by obligation - the military’s own photographers. Men such as USMC G/SGT Steve Stibbens (1936-2020) the first man that Stars & Stripes sent to Vietnam. Joining the USMC in 1953, Stibbens arrived with special forces advisors in 1962. He did four years in country, left the Marines and then went back to Vietnam for a year as a civilian for Associated Press (AP). Afterwards, he stuck with AP in his native Texas, where he died a few years ago. According to his daughter, he never talked much about Vietnam.

S/SGT David Savanuck (1946-69) did not survive. A native of Baltimore, he enlisted in 1967 and a year later found himself in West Germany. Dissatisfied, he agitated to be posted to Vietnam and was granted his wish in summer 1968 with an assignment to the 23rd Artillery at Phu Loi near Saigon. The following spring, newly transferred to Stars & Stripes, he was camped for the night with an armoured cavalry unit near Cam Lo, Quang Tai when they were bounced by the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). Savanuck assumed the role of medic and was attending on a wounded colleague when they were both shot dead. Savanuck had written, "I shall not be content with anything less than what is true. I intend to be the best." There is a memorial library named for him at the US Defence Information School at Fort George, Maryland.

Dennis Fisher was also a Marine NCO. He submitted to the Corps in-country publication Sea Tiger and the Corps-wide Leatherneck. His testimony to the US National Archives is both stirring and moving7. Quoting from his interview, “During the heavy fighting in 1967 and 1968 combat photographers from the 1st and 3rd Marine Divisions were being killed or wounded at an alarming rate….photographers who spent a lot of time in the field……would be wounded sooner or later. During the Vietnam war twelve Marine combat photographers died. One was killed in a commercial plane crash coming back from R&R and another died of a stroke but the other ten were killed in action. Seven of those ten were killed in 1968 making it the deadliest year for Marine photographers”. Dennis Fisher remained faithful to his vocation and was later even engaged by Hollywood. These days, spends his time promoting his beloved Corps and tracking down former Marines to offer photos of themselves to them or to their families.

By the same token, we also salute the photographers of South Vietnamese forces, and of the North Vietnamese Army too - though the latter were more often engaged in photographing training and staged engagements.

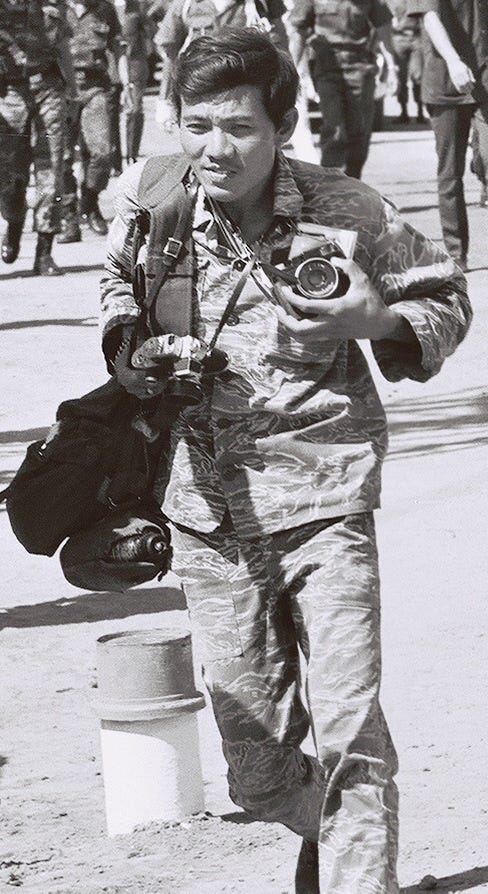

ARVN SGT Tu Vu - 1970

Credit: Unknown

There is certainly research to be done and another piece written about US military’s photographers in Vietnam, however, here and now, this one must concentrate on the civilian photographers who perished 54yrs ago today.

To understand how these men came to be in that helicopter all those years ago, some background knowledge of the conflict in Vietnam is necessary, but there is only space for an abbreviated outline - one that takes us up to the day of the fateful flight:

1945 - after the WWII Japanese occupation, the French moves to restore their 90yr colonial rule. However, Communist Ho Chi Minh has other ideas and declares an independent Vietnamese state in the north. France calls it ‘a free state within a French union’.

Ho Chi Minh was indeed a communist. However, in front of that, he was a Vietnamese nationalist who was determined to forge a nation that was independent of all foreign interference - French, American, Chinese or Soviet. Washington either failed to understand this, or else did not trust Ho’s word, or his ability, to keep the Chinese and Soviets at arm’s length - or perhaps his ability to survive without being deposed. The Americans feared a vacuum that would be filled by Peking or Moscow. History tells us that either they under-estimated the Vietnamese will to fight, or they believed that victory would require a long war of attrition - one that for various reasons, including perhaps corporate, they were willing to accommodate.

1946-56 - relations between Paris and Hanoi deteriorate and war breaks out. In 1954, despite US support the French suffer ignominious defeat. Peace is forged in Geneva - France pledges to leave Vietnam and the boundary between the Communist ‘North’ and free ‘South’ is negotiated - until elections are held the demarcation zone is the 17th Parallel. The agreement pledges an amnesty of free passage and 300,000 Christians in the North flee south, but Ho instructs Communists NOT to move north. President Eisenhower outlines ‘Domino Theory’. In 1960, Ho’s sleepers become the National Liberation Front (NLF). The Diem regime is installed and the elections are cancelled. Diem calls the NLF the Viet Cong (VC)…’cong’ = communist.

1957-59 - the VC begin terror attacks in the South killing local officials and planting bombs in Saigon. The Diem regime proves itself totally corrupt. North Vietnamese forces start receiving military aid along the ‘Ho Chi Minh Trail’, from SE Vietnam through Cambodia and Laos.

1960-62 - Democrat Kennedy is elected US president, he adopts the hawkish Republican anti-communist policy. US military ‘advisors’ in Vietnam number 700. In 1961 VP Johnson visits Diem and calls him ‘the Churchill of Asia’. It later emerges that his regime had misappropriated $2bn of aid. US initiates multiple ‘hearts and minds’, surveillance, pilot training and defoliation projects. By year’s end there are 3,000 US and a few hundred Australian ‘advisors’ in Vietnam.

1963 - despite US advice and training, when ARVN (South) forces attack the VC at Ap Bac, the first assault of the war is a calamity. Buddhists revolt against Diem. Washington decides that he is more Al Capone than Churchill and sanction his removal. Diem (and his brother) are assassinated three weeks before Kennedy.

1964 - South Vietnam becomes a military regime. US establishes a broad counter-insurgency operation. The Gulf of Tonkin Incident (USS Maddox is ‘attacked’ by North Vietnamese torpedo boats) results in a Congressional resolution authorising, “all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression”. VC attack Bien Hoa air base. Johnson wins the full presidency.

1965 - the USAF base at Pleiku is attacked by the VC. In response, Washington escalates the conflict. Operation Rolling Thunder - the bombing of North Vietnam - begins. US Marines land at Da Nang. The ground war is expanded and ‘search and destroy missions commence. Famousy, the Air Cavalry fights the Battle of Ia Trang Valley. By year’s end there are 200,000 US troops in Vietnam.

1966-67 - on land, in the air, on water and clandestinely, the war expands exponentially. Operations Cedar Falls, Pershing and Junction City (the war’s only parachute drop) develop the ground war even further. By the end of 1967, there are nearly 500,00 US personnel in Vietnam. US forces’ discipline begins to deteriorate, whilst citizens’ uneasiness begins to manifest itself more strongly.

1968 - at Khe Sanh, and then over Tet the NVA and VC launch attacks along a broad front. The VC and NVA will not lie down and Washington is stymied. Peace talks commence in Paris. The bombing of North Vietnam ceases, US air strategy is directed more at the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Westmoreland, the US C-in-C Vietnam, is replaced by Abrams. Nixon becomes president.

1969 - the NVA and VC launch another Tet offensive. Nixon authorises the bombing of neutral Cambodia. US forces reach a peak of 550,000. Washington initiates its ‘Vietnamisation’ policy, essentially, the incremental reduction of US resources in favour of the South Vietnamese ‘running the show’. Ho Chi Minh dies. When news of the My Lai Massacre breaks the autumn sees mass protests across the USA, including a huge one in Washington.

1970 - Further troop drawdowns are announced but Cambodia is invaded. This results in protest and deadly violence on a number of US university campuses. The last major battle between US and NVA ground forces takes place at FSB Ripcord in the A Shau Valley. The 101st Airborne hold out but withdraw.

1971 - The Cooper-Church Amendment, forbidding US ground troops to enter Cambodia and Laos, becomes law. Congress repeals the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution - the permission for ‘all necessary means’ is withdrawn. Further moves to restrict the scope and funding of operations in Vietnam are in the pipeline. Operation Lam Son 719 - the South Vietnamese invasion of Laos begins.

The invasion of Cambodia had caused serious socio-political turbulence in America, and indeed had provoked disquiet around the world. So, even without US ground forces, Operation Lam Son 719 was very significant, and there was no question that the press corps would have considered it highly newsworthy.

The operation launched on 8th February, and there had been a news embargo, but the general fact of the invasion had been suspected for months. The NVA had 60,000 troops waiting to counter it, but more significantly for this story, they had also installed 800 anti-aircraft weapons in the border zone.

Who were the men who were lost on 10th February 1971?

Henry Frank Leslie ‘Larry’ Burrows was born the son of a railway worker in Finsbury Park, London on 29th May 1926. Just as WWII broke out his grandmother bought him a camera. After a short time as an errand boy with the Daily Express, in October 1942 aged 16yrs, he joined LIFE’s London office in a similar capacity, but soon became a dark-room assistant. There, he would have come into contact with the likes of Robert Capa8, George Rodger9 and other well-known WWII photographers.

Wishing to serve the war effort, and perhaps enjoy an adventure, Burrows applied to join the Merchant Navy but was rejected on grounds of eyesight. Instead he was directed to the coal-mines as a ‘Bevin Boy’10. Life under-ground caused him such great anxiety that after 16 months the people at LIFE lobbied some contacts to get him re-assigned. He returned to the LIFE offices and picked-up on developing his photographic skills. Among his tasks was the development of film that had been taken during the invasion of France. He was handling history, and one is sure that this fact did not escape this intelligent and thoughtful young man.

In 1945, LIFE handed him his first practical assignment, covering a conference of foreign ministers. He was also keenly interested in photographing museum pieces and works of art, and photographing ‘still life’ helped him perfect his skills. Burrows also engaged in photographing the street-scenes of post-war Britain, thereby learning how to capture the human condition.

He must have appeared verypromising, for in 1947 Capa asked Burrows to join him in the new independent bureau of photographers - called Magnum11 - that he and Rodger were establishing along with Henri Cartier-Bresson12 and David Seymour13

These men were the twentieth century’s godfathers of war photography14, but Burrows declined. Many years later, Burrows’s son stated that he felt that he would learn more sticking with the stable, settled operation at LIFE. Though perhaps there was another motive too, in that this quiet, honourable and diligent young man decided to remain loyal to the people who had saved him from the torment of the coal-mine.

At around this time in summer 1947, aged 21yrs, after a short romance, Burrows married his work colleague Vicki Dickens. Throughout the post-war period, Burrows worked in London, photographing street-scenes and significant personalities of the age such as Churchill, Attlee and various authors and actors such as Snow and Maugham, and Olivier, Monroe and Bardot. He also went on overseas assignments to cover the beauty of architectural and natural wonders such as the Taj Mahal, the wildlife in Indonesia and Australia. He also shot numerous conflicts and trouble-spots such as Suez, Cyprus, India and Congo.

By summer 1962, Burrows was a highly accomplished all-rounder and one of LIFE’s masthead assets. He was offered a choice of assignments, and opted for SE Asia and the fracturing situation in Vietnam. He moved his family to Hong Kong and lived on Headland Rd., Repulse Bay.

At this point he began travelling to Saigon and hooked-up with Horst Faas. Actually, that is incorrect for Larry Burrows never really ‘hooked-up’ with anyone.

Whilst he generated a reputation for being gentlemanly and helpful, particularly to ‘green horns’, Burrows was single-minded in pursuit of the best stories and shots and had a good nose for sniffing them out. He kept his ideas to himself and his colleagues would often arrive at coffee meets to find that Burrows had gone ‘up country’ to work on a project he had developed. He was also quite protective of his ‘turf’ and would politely assert his ‘rights’ when he felt his toes were being trodden on. He was the ‘senior man’ and he believed in the ‘pecking order’. As time passed, perhaps only Horst Faas and Henri Huet were colleagues he might defer to. Nevertheless, everyone loved Larry Burrows for the way he carried himself and dealt with people. The soldiers loved him too for “never getting in the way and never imposing”.

Fellow professionals also respected his technical excellence and were in awe of the way he went about his work, both in the field and back at the office. Larry Burrows was the consummate professional who, even for a professional, took meticulous care of his cameras and equipment. It was said that he had custom-designed his own steel cases, and always insisted on having a twin room, one bed for himself, and one for his cameras. Returning from the field, unlike his colleagues, Burrows would head for his room and not the bar, where, freshly showered he would clean his equipment before eventually putting on a collar-and-tie and descending for supper and a few drinks.

Larry Burrows compiled an incredible body of work on the VW: January 1963 - ‘The Vicious Fighting in Vietnam’; 1964 - ‘Alert in Vietnam, US Special Forces’; 1965 - ‘One Ride with Yankee Papa 13’; and 1966 - ‘Invasion DMZ, Runs into the Marines’, which included the photograph called ‘Reaching Out’ which won him a third Overseas Press Club's Robert Capa Gold Medal Award when it was published after his death, to go with those won in 1963 and 1965. He was slightly unusual in that he shot in colour as much, if not more, than he shot in black & white. Burrows was unique.

Operation Prairie - G/SGT Jeremiah Purdie ‘Reaching Out’ to One of his Boys - 5th October 1966

Credit: Larry Burrows

In January 1971, he and Horst Faas were both in Calcutta working separately on the political instability (Burrows was almost killed by a terrorist bomb), the slums and Mother Theresa. Their respective agencies called them back to Saigon to cover Lam Son 719. Faas had no visa and had to go to Singapore to get one. Taking these extra days saved his life. Otherwise, he would have probably taken 23yr old Potter’s seat in the Huey, and thus in one incident, the world would have lost the three most prominent photographers of the Vietnam War.

Upon arrival in Saigon, Burrows discovered that Huet was already on his way north to the rendezvous and went after him. As the ARVN Lam Son 719 convoy headed towards the border it was erroneously attacked by a US Navy A-6 Intruder, and six soldiers were killed with over 50 wounded. Burrows took photos whilst simultaneously helping to drag wounded men away from a burning ammunition vehicle.

At this point just three days before his death young Roger Mattingley took this photo.

Larry Burrows (1926-1971) - Photographer - 7th February 1971

Credit: Roger Mattingley

Mattingley was a very junior Army photographer whose career choice had been inspired by Burrows’s 1965 ‘Yankee Papa 13’ essay. As inexperienced as he was, he certainly captured a poignant shot of his hero. Burrows had been in and out of Vietnam for nine years, he had said that he would keep covering the conflict until it ended - and had he lived he surely would have - but the photograph indicates a perceptible weariness.

Perhaps Burrows’s most touching encomium was provided by David Halberstam in ‘Requiem’, "I must mention Larry Burrows in particular. To us younger men who had not yet earned reputations, he was a sainted figure. He was a truly beautiful man, modest, graceful, a star who never behaved like one. He was generous to all, a man who gave lessons to his colleagues not just on how to take photographs but, more important, on how to behave like a human being, how to be both colleague and mentor. Our experience of the star system in photography was, until we met him, not necessarily a happy one; all too often talent and ego seemed to come together in equal amounts. We were touched by Larry: How could someone so talented be so graceful?"

Henri Gilles Huet - was born in Vietnam in 1927, in Dalat in the higher lands of central south Vietnam. His father was a French road and bridge engineer who had taken up with a Vietnamese woman. She was from a family that owned a 1000-acre farm plantation that grew coffee and fruit and kept dairy animals. Gilles Huet did not marry the mother of his three sons and daughter, and their children did not know her name. As so often when European and Asian blood mixes any offspring are attractive and Henri Huet was exceedingly handsome.

When ‘Maman’ died in 1937, the three older boys had already been living with his father’s family near Rennes in Brittany for some years, and then their sister joined them. The children had not had warm relationships with either parent, and their adoptive parents were distant too.

Huet was 17yrs old when the Allies invaded and liberated France. Good at soccer, but quite artistic he attended a prestigious art school in Rennes, but the maelstrom of war and the flux of peace skewed his life. In his early-20s he followed his older brother into French military service. After training he became a taker of aerial photos for battle planning, and in 1950, he elected to return to Indochina.

In 1952, Huet completed his service and was discharged but chose to remain in situ. He felt comfortable there, he had reconnected with his father and now had a valuable trade/profession. He set himself up as a freelance. As Vietnam’s political stability dissolved, Huet received commissions from the US embassy and also sold work to Paris-Match. In the late-1950s he acquired a wife - a Russian-Vietnamese - and two children.

In 1965 with war a hard reality, Huet’s well-regarded reputation saw him picked-up by UPI; but soon afterwards, Eddie Adams, younger than Huet but already established at AP persuaded him to transfer his loyalty. This trebled his pay, and the money was useful for he had to send a good proportion of it to New Caledonia. Perhaps for the children’s’ safety, but probably also because of a crumbling marriage, his wife had relocated to the French Pacific.

Quiet, introspective and teetotal, Huet was a superb technician with his camera. He would go on to become something of a legend with both the pressmen in Saigon and also with the soldiers in the field.

In early-1966, on assignment with the 7th (Air) Cavalry at An Thi, Huet and Bob Poos shared a very hairy few days. Under heavy attack, the two photographers mucked-in with the soldiers to retrieve and tend the wounded. The famous Colonel ‘Hal’ Moore was highly appreciative of their efforts, Huet’s in particular; but not only had Henri Huet carried wounded men to safety, but he had also taken some excellent photos.

“I hear Henri’s got some pretty good stuff” said Larry Burrows as he visited the AP office soon after Huet’s material had been developed. Upon seeing the images, Burrows declared that a couple in particular were worthy of a LIFE cover, and pledged to procure this outcome. This he did, and Huet’s photo appeared, and ultimately earned him the Overseas Press Club's Capa Gold Medal for 1966 for - in their traditional citation - “superlative still photography requiring exceptional courage and enterprise.”

The following year, having returned from the award ceremony is US, Huet was in the field again. This time with the Marines - and Dana Stone - up in Con Thien a hill-fort near the south-north border. In prolonged combat, the base perimeter was breached and there was also heavy artillery/mortar fire. Huet received shrapnel woulds that badly mangled his leg, so much so that he was ultimately airlifted to US for surgery - where, legend has it, he was nearly killed again by a careless anaesthetist. Legend also has it that a Marine had given his life to shield Huet from the full force of the original blast.

Henri Huet was written off sick for months. After regaining his mobility, he took a long holiday. This did not involve his family, but a Belgian AFP staff member called Cecile Schrouben.

Returning to Saigon in spring 1968, Huet swiftly re-adopted his seemingly carefree attitude in the field. His bosses suggested that he take another break, and he accepted a posting to Japan. He left Vietnam in June 1969, but by the end of the year he was bored rigid and perhaps also a little depressed. This mood may have been amplified after Christmas when he received a ‘Dear John’ letter from Cecile. He shared the news with his neighbour a Swedish freelance art writer called Inger-Johanne Holmboe. They struck up a ‘words-and-pictures’ team and became an item, but Huet’s mind was often back in Indochina.

In spring 1970, US and ARVN troops invaded SE Cambodia and Huet was soon back in the thick of things. That said, later during the summer, he and Holmboe visited friends around SE Asia, and at Christmas they went to New Caledonia to catch up with his family. It was not a successful trip. The situation his children were in worried Huet, and in anticipation of his demise he made Holmboe his executor with written instructions and money to provide for them. When he had this conversation with Holmboe, Henri Huet had just a few weeks to live.

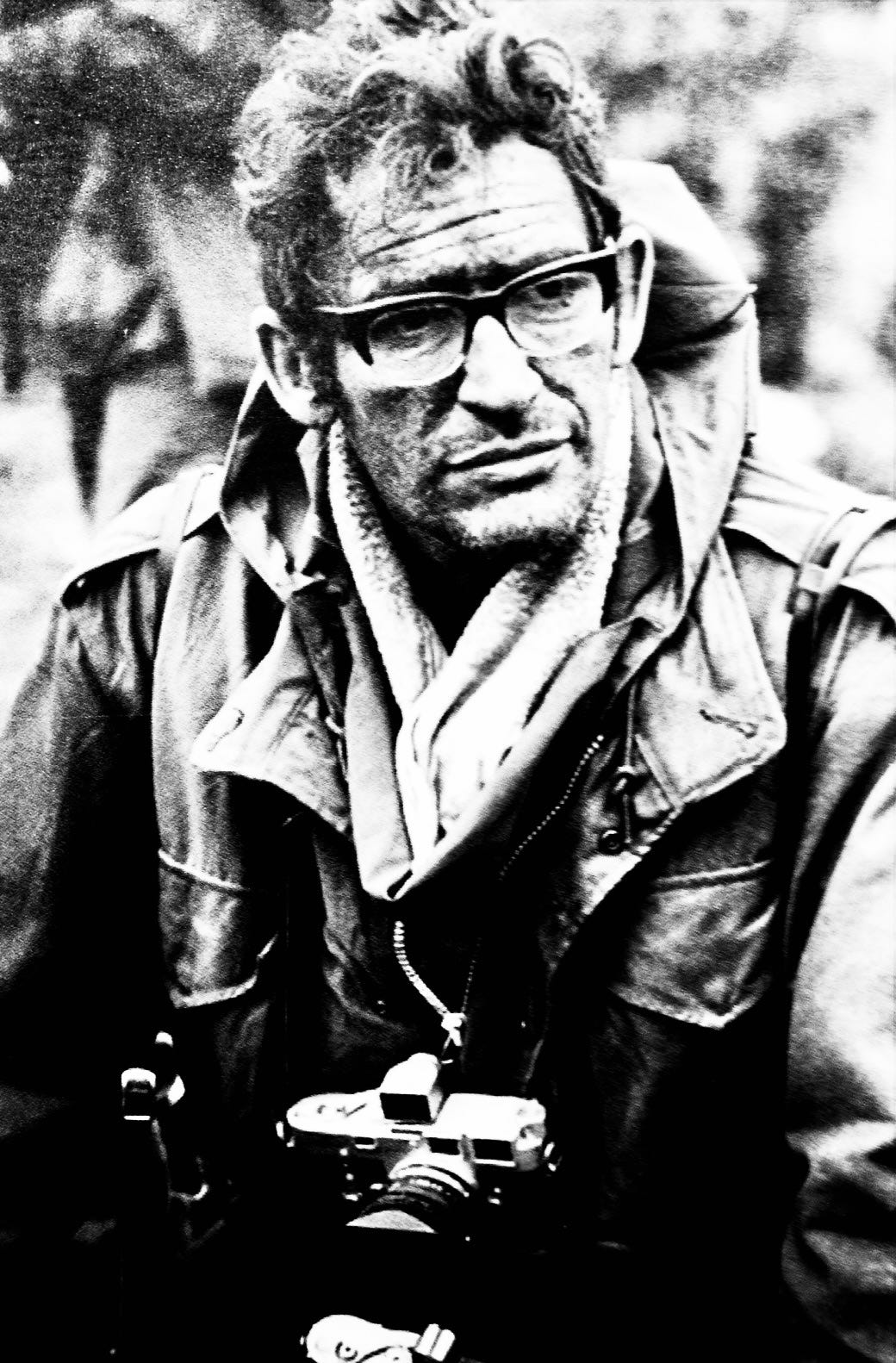

Henri Huet - Near Saigon - 1966

Credit: AP

Rumours of the invasion of Laos were circulating strongly and Huet was determined to cover it even though he needed to make a ‘visa run’. He postponed the obligation and travelled north to the rendezvous, Ham Nghi, pledging to return to Saigon after he had shot a couple of days of action. By this time, Burrows had found him. It seemed that the following day, the bad weather would probably clear to allow a helicopter sweep over the front-lines - and it did.

Of Huet’s work, Horst Faas would relate, “I always knew from handling his film on a daily basis that Henri was a great photographer, but I didn’t realise how great until I saw his body of work in its entirety. He may have been the best of all of us”.

Kent Biddle Potter was just 23yrs old when he died. Born into a Quaker household in Awbury just north of Philadelphia, he was strong in both intellect and character. However, in spring 1961, his family was visited by tragedy when his mother took her own life with sleeping pills that she had sent her son to collect. His father seemed to hold this against him and the pair’s relationship deteriorated. Potter senior became a withdrawn pacifist, whilst Potter junior became a withdrawn person who had determined to join the Army.

Before he could do so, fate intervened. His path crossed that of Dirck Halstead UPI’s photo man in the city, and he began working at there in 1963. He took to action photography like a duck to water, and won awards for his photos of a bank robbery, having braved gunfire to get his pictures.

In spring 1966, he enlisted in the USMC Reserve, his plan may have been to keep his day job to build experience whilst getting his foot in the door of the military. In this way he had a chance of becoming a war photographer. Whether this was a strong ambition, a desire for adventure, or a compromise between his Quaker heritage that forbade killing and a desire to serve, only he would have known, for habitually, Kent Potter kept his thoughts to himself.

By 1967, both Halstead and his replacement Frank Johnston had gone to Vietnam and Potter was running the Philly office. In the course of this he came to know Bill Snead who UPI appointed Saigon chief in late-1967. Seeing him off at the airport, Potter implored Snead to send for him. Months later, in the weeks after the Tet Offensive of 1968, UPI lost two photographers: Bill Hall was seriously wounded and Hiromichi Mine was killed. Snead duly arranged Potter as a replacement.

Before travelling to Vietnam Potter had to acquire a discharge from the Marines, and miraculously the Corps agreed to his request on condition that he remained in Vietnam for 18 months. He arrived in Vietnam in April 1968 just before he turned 21yrs.

His first weeks saw the deaths of five photographers and journalists, four being gunned down when their Mini Moke ran into Viet Cong guerrillas in Saigon’s Chinese quarter Cholon; then Charlie Eggleston, someone Potter had made friends with was also shot dead. A few weeks later, Potter was present when a building housing a gaggle of military photographers was blown up. Several were killed, but, under fire, Potter helped drag the wounded out.

In Lost Over Laos, Faas and Pyle relate that over the 18 months that followed, Kent Potter became a rather difficult and sometimes arrogant person. He was also indulging in drugs with some of the younger ‘gonzo’ photographers such as Tim Page, Dana Stone and Sean Flynn. Most likely, he was putting on a front to cover certain - entirely understandable - anxieties. We’ll leave this matter unexplored, except to say that he must’ve been competent at his job because in summer 1969, UPI made him Saigon photo chief.

It is said that in all aspects of life in Vietnam Potter was keen to impress Larry Burrows. It is also said that by the second half of 1970, his hero had had a positive influence on the way he conducted himself. One imagines Burrows talking sympathetically and sensibly to a colleague half his age.

Two of Potter’s friends; Tom Martin, a school-friend resident in Bangkok who saw him regularly, and the other an old girlfriend, Ann Bathgate, he had remained in contact with noticed his erratic desire to challenge, confront and shock. The latter questioned why Potter had remained in Vietnam after his ‘18 months’ were up, and concluded that he was mourning the death of his mother and fractured relationship with his father. Potter seemed quite willing to lose his life in for his profession. Probably, what should be understood most about Potter is that he was very young - a few years older than the average US soldier in Vietnam, but still a very young fellow with a lot on his plate.

When Tom Martin cleaned his friend’s Bangkok flat out he found contact sheets and negatives, and he later commented, “These photographs showed maturity beyond (his early career in Philadelphia). In Vietnam, he had mastered composition and lighting…..he blended art and content to tell a poignant and lasting story”.

Keisaburo Shimamoto was Japanese but was born in Seoul, South Korea in 1937. As Faas and Pyle state, he had known war and been surrounded by soldiers for all of his early life. Escaping the bombing of Tokyo by decamping to the hills, he was deeply affected by Japan’s surrender, and later felt humiliated by the lengthy occupation of his country.

By 1959 he had a degree in Russian and was contemplating a career. His older brother Kenro was a journalist and so Shimamoto followed suit. He discovered a natural aptitude for photography, and also found a mentor in Akihiko Okamura a flamboyant freelancer who had made a stellar reputation as Japan’s premier war photographer.

In 1965, Okamura was back in Vietnam, and Shimamoto was sent to join him. He would be there for two years until summer 1967. He generated a name for being cool under fire and for a stereotypical Asian inscrutability. In truth, Shimamoto was a cheerful, witty character with an active mind. The livelier traits of his personality he reserved for his boozy gatherings with the Japanese press corps.

After just over six months break back in Tokyo, in early-1968 and by now working for the French agency Gamma, Shimamoto returned to Vietnam and did another two years.

When he went back for a third tour in early-1970, he was mostly shooting for Newsweek. That Christmas, Shimamoto’s wife Yuko joined him in Saigon and it is believed that having saved some money, she suggested that they start a restaurant business in Tokyo. It is thought that Lam Son 719 was going to be his final job before going home.

Shimamoto ought not to have been on the Huey. He had travelled from Saigon to Khe San to meet Okamura, but typically, the self-absorbed star had gone off to do his own thing. As a consequence, Shimamoto ventured to Ham Nghi where he found Burrows and Huet waiting for that helicopter.

SGT Tu Vu - regrettably, apart from the photograph above, nothing could be discovered about him.

Four miles east of the Lao border, Ham Nghi was the forward command post for the operation. In command was General Lam Hoang Xuan. He was in command because, rather than being the most competent general, he was a staunch ally of the Vietnamese president. It is likely that he wanted foreign journalists to accompany his first inspection of the front-line for PR reasons, and five helicopters were waiting at Ham Nghi to convey the press.

One of the military photographers there was Corporal Sergio Ortiz15. He had been assigned to photograph the comings and goings of USMC helicopters at work on the operation. He knew Burrows and when he saw him moving towards the heli-pad he went to say hello. Ever the gentleman the senior man introduced Ortiz to Huet, Potter and Shimamoto as an ‘equal’, and Ortiz treasures the few minutes conversation they had. Having said goodbye he turned and snapped a couple of frames for a personnel souvenir.

Potter had suggested to Ortiz that he join them, but recall that US military personnel were strictly prohibited from crossing the border into Laos. So his life was spared. As was Michael Putzel’s who had been sent by AP to remind Henry Huet about his visa. Putzel offered to take his place to enable him to sort it out, but Huet declined. David Burnett could have lost his life too - a recent arrival in Vietnam, he had tried to bluster his way onto the trip for Time, but the officer in charge held his ground.

Hal Ellithorpe’s life was also spared. He was a scribe for LIFE and planned to write the words to accompany Burrows’s pictures. Fortunately for him, the pilot found that the aircraft was overloaded and asked one of the journalists to get off. Burrows looked at Ellithorpe and said, “LIFE is a picture magazine Hal, you’ll have to make it another time”. Ellithorpe grunted and got off.

There were five Huey’s making the trip. General Lam had an itinerary of three stops. After the first, the next was a further 14 miles away. For some reason, General Lam’s Huey took off quicker than the other four which became detached. As a consequence, they drifted slightly off course.

Watching them from half-a-mile away was a US chopper pilot legend called Jim Newman, he knew from recent experience that they were headed towards a cluster of anti-aircraft guns and issued a radio warning. It was too late. The first of the four, the one carrying our subjects was hit, exploded and dropped from the sky - as did the second of the four soon afterwards. If the crews and passengers were not dead before they hit the ground, they were soon afterwards. From routine to calamity within a few minutes.

In April 1995, Richard Pyle and Horst Faas were contacted by a US Army team assigned to battle-field investigations in search of the remains of missing servicemen. They were looking into ‘Case 2062’ - the events of 10th February 1971, and were determined to find the crash site.

In 1998, with a firm indication of success, Pyle and Faas went back to Vietnam and were soon at the excavation site in Laos. To cut a heartwarming story short, investigations had confirmed that the site was where the Huey went down and it was going to be dug. That same year, Shimamoto’s older brother and his 95yr old mother made a pilgrimage to the site to conduct a Buddhist ceremony.

Amongst the numerous small artefacts that were positively identifiable was the top of a Leica camera that Larry Burrows had purchased in London in 1962, and also a christening medallion engraved with a name and a date…….16-6-1947 and Cecile.

All told, between 1945 and 1975, 135 photographers and reporters were lost in the long conflict in Vietnam.

Surely, the Vietnam War represents the zenith of combat photography: the authorities allowed them much leeway, there was an unspoken agreement that the soldiers had no obligation to defend them, but the photographers would help the wounded. They seldom manufactured situations and would not exploit their subjects; they took fine, honest photographs, put themselves in harm’s way to get them and somehow managed to maintain their humanity.

Well-used as we are to the portrayal of war on television and film, it may have escaped some that almost every individual photograph represents sacrifice. Each individual photographer had eschewed a stable family life, every personal comfort imaginable and of course a safe environment. One doubts that the likes of Huw Edwards and Clive Myrie are fit to carry their camera boxes.

Larry Burrows’s enduring images from his March 1965 journey can be found here.

Some of Henri Huet’s very best images can be found here.

For the likes of me generally interested in the world and its inhabitants an excellent piece - illuminating and poignant. Pity there’s nothing on Sgt Vu Tu - maybe a trip to Saigon to research?

And, since you mention it, it has long seemed to me that, other than that special kind of heroic recklessness and bravery, looks were the other entry qualification to the ranks of the war photographer (and war journalist) clique. From the rugged such as Rodger and Burrows (and maybe just about Faas if I’m being charitable), to the enviably handsome like Huet, Flynn (impeccable genetics) and of course Capa himself, who could easily have been a star on the other side of the camera.

I know, I was just talking about Burrows's ordinary appearance. That's my point, they were just ordinary blokes who did some extraordinary things.