First Half Line-out - Wales vs England - Cardiff 12th April 1969

Credit: Unknown

These days the championship of European rugby, now the Six Nations, seldom intrudes into April. Indeed, this year, the Wales vs England fixture on 12th March was the final weekend of this year’s tournament.

Whilst last month ENG enjoyed a very handsome victory in Cardiff, the 1969 match saw Wales dish out a painful 30-9 hammering of England.

In doing so, Wales marked the emergence of their great side of the 1970s which would enjoy a 10-yr period of dominance in Europe. They won the championship in 1969, and Grand Slams would follow in 1971, 1976 and 1978, with other championships secured in 1971, 19721, 19732, 1975 and 1979.

Without doubt, they were an incredibly special generation - or two - of players, and were the bedrock of the legendary British Lions teams of the era. Indeed, on four Lions tours 1971-80, over 40% of all players were Welsh.

In contrast, the period was a dismal nadir for England, with perhaps only David Duckham capable of matching the brilliant panache of the Welsh. Indeed, he was so good the Welsh called him ‘Dai’.

So, for an Englishman there are only two reasons to like this photo. The first concerns a nostalgic reverence for the unregulated chaos that was the line-out until 1999 when lifting was officially sanctioned. In those times, the line-out usually resembled two gangs of blokes trying to play volley-ball keepy-uppy with a wet salmon, and this picture shows the hurly-burly nonsense in all its flailing inglory.

The second reason is for the workmen sat watching the match high-up in the semi-constructed stand. It’s a great image and partially resembles those construction workers eating lunch whilst sat on a girder of that New York skyscraper in 1932.

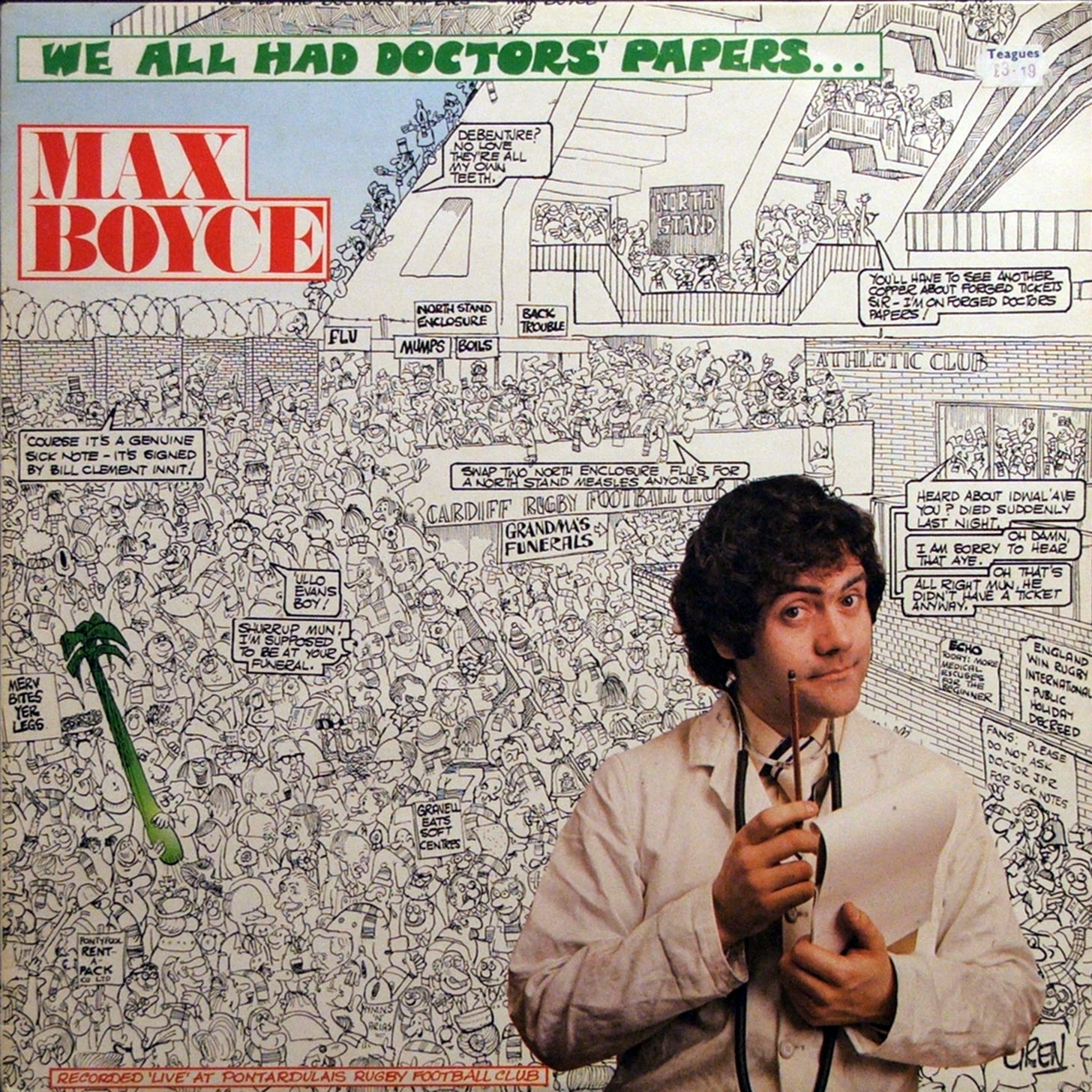

If indeed that is if they were genuine workmen and not a bunch of enterprising fellows who had gone to the match ticketless, but in disguise. In those days - as Max Boyce hinted3 - the lax security allowed the possibility of such rascally behaviour. Even if they were genuine site workers, one cannot fail to appreciate their chutzpah in persuading their gaffer to schedule them to work on the Saturday of an international.

On a sunny day but sticky surface, Wales enjoyed their comprehensive victory with the Gareth Edwards - Barry John axis in dominant mood, and left-wing Maurice Richards scoring four tries. A record-equaling feat that probably helped seal his code-switching deal with Salford RLFC.

Also in the Wales line-up that day were Wales and British Lions greats JPR Williams and Mervyn Davies, both in their debut seasons. Another great, with just one cap at that point, Phil Bennett was on the bench.

Legend has it that Wales thought that there would be mileage in targeting England’s scrum-half Trevor Wintle - especially at line-out time. This relatively unmarshalled phase of the game allowed sides an even chance of getting away with sneaky gamesmanship that continued until the referee stopped it. In the melée of the line-out, it was not an unknown tactic at the time to deliberately knock the ball forward into the opponent’s territory and then rush through on the scrum-half who had to scramble swiftly to get to the ball away or else be trampled to a pulp.

Legend has it that Wales adopted this tactic in this game, and called ‘Trevor’ as a signal for it to be put into operation - sadly for the away side, Referee D’Arcy failed to pick it up and poor Trevor Wintle got pounded, and never played for England again.

Despite Maurice Richards’s four tries, the day belonged to Barry John. The maestro was a shadow that England simply could not catch, and it is a great shame that with the new stadium half-built only 29,000 people saw his performance.

Many say that John who died in February 2024 was the greatest player who ever lived. It’s a little difficult to award that title to a man who eschewed tackling and rough stuff, but in this purist’s eyes John was definitely the world’s most graceful and accomplished player. There was nothing he couldn’t do with a rugby ball, and his opponents were further disadvantaged by the fact that John himself did not really know what he was going to do with it until he had it in his hand. Pure instinctive magic that is rarely possible these days of dominant defences.

The full bowl of the new Cardiff Arms Park was only completed in April 1984, a full fifteen years after this photograph was taken. One hopes that the workers were able to continue getting rostered to work on match Saturdays.